Ormrod, W. Mark, Bart Lambert, and Jonathan Mackman. Immigrant England, 1300-1550. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019.

The general notion that the Middle Ages were a time of static experience for the people living through them is an idea that is countered by W. Mark Ormrod, Bart Lambert, and Jonathan Mackman in Immigrant England, 1300-1550, their examination of the immigrant experience in England through the end of the medieval period. The conclusions they are able to draw propose that England during this time period was a “viable – and in many cases a positively attractive – place to move to” for foreigners seeking opportunity (37). The work is the result of a collaboration among Ormrod, Professor of History at the University of York, who led the project, and Lambert and Mackman who assisted with research. The book is connected to a larger research project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom that produced a research database and website (www.englandsimmigrants.com), where one can access and study the raw data on which the book is constructed.

The foundation of the work rests primarily on two types of documentation, pulling heavily from the files of the Exchequer and Chancery courts. First, the authors used records of a special tax known as the alien subsidy, which was applied to foreigners residing in England and was collected at different times between 1440 and 1487. The most important aspect of the subsidy was that it served as a “crude form of alien registration” (6), thereby providing a crucial resource to researchers as to how many immigrants were in England during the span in which the subsidy was applied, where they came from, and what type of work they did. While there is much inconsistency in the documents, tax officials many times recorded the nationality of aliens, and the researchers were also able to draw conclusions about origins based on the recorded surnames of aliens. Second, the authors collected letters of denization which allowed foreigners who intended to stay in England the rights to use English courts and to hold property in return for swearing an oath of fealty to the king of England. While denization was never widely used, it does provide information on the backgrounds and activities of immigrants.

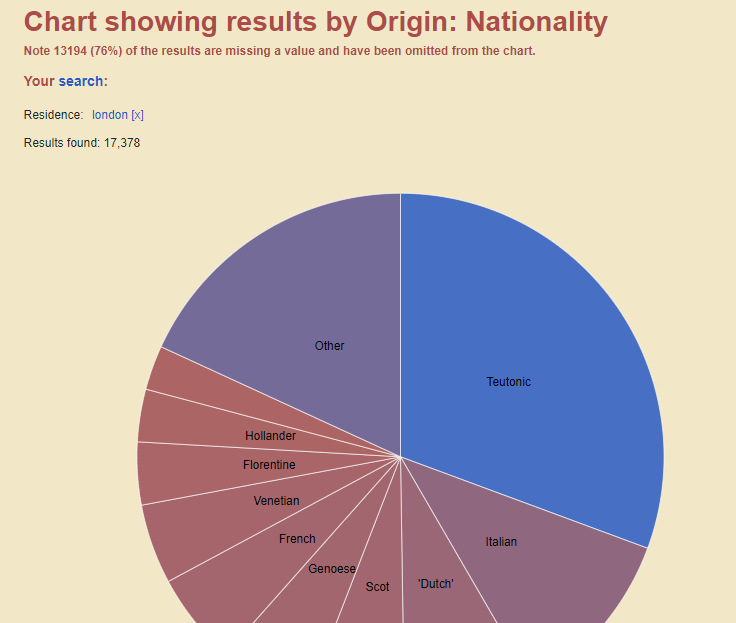

The findings provided by these sources show that immigrants were coming to England from a wide variety of places, from both within the British Isles – Wales, Ireland, and Scotland, and from overseas locales such as France, Italy, and the Low Countries. And while there were higher concentrations of immigrants in the larger English cities, the records show that immigrants were living in every corner of the country, even in most rural areas. The authors note this as an important finding, for while the degree of interaction varied, “virtually all the indigenous population of England had some degree of personal knowledge of foreigners” (69). The finding also suggests a high degree of mobility in the British Isles and Europe, and a robust degree of migration that popular views may not associate with this time period. Nearly all native English people, even those who lived in rural communities, would likely have experienced some level of interaction or relationship with foreigners. The authors additionally attempt to illuminate groups that are often ignored in most existing historiography, such as women, religious minorities like Jews and Muslims, and the low-status poor, who mostly show in the alien subsidy returns under the catch-all term ‘servant’, making it difficult to determine specific information about their circumstances. Though these groups certainly existed, little of their experience was documented, leaving their lives in the gaps of the archive. Notwithstanding the archival silences concerning women and minorities, an issue which is admittedly a larger problem within historiography in general, the evidence suggests that, overall, opportunities were limited for women and minorities, particularly if they were also immigrants.

After establishing that thousands of immigrants were in England in the late Middle Ages, the authors examine what brought them there and what they did once in England. After multiple outbreaks of the plague during the Black Death, there was major depopulation in England which caused labor shortages and resulting wage increases. Higher wages resulted in more disposable income and the appearance of a consumer economy. As more goods were produced, manufacturing increased and foreign workers were attracted by the economic opportunities of this situation, not to mention the legal benefits offered by denization. Skilled craftsmen who immigrated to England for work often employed fellow immigrants as workers, sustaining the flow of immigration. The authors detail a number of industries in which immigrant workers played a role, such as the clothing industry, building materials, and beer brewing. At times, the prevalence of immigrant craftsmen and merchants, and the popularity of their goods, caused tension between them and native workers. The authors describe several instances when the tension between immigrants and English natives boiled over into violence in order to make the point that violent outbursts of this kind were relatively rare and were not the result of pervasive anti-alien sentiment, but arose more from general economic and political unease that was occasionally directed toward immigrants.

The work of Immigrant England is impressive due to the amount of knowledge it is able to draw from the alien subsidy records and other associated government documents. The majority of the book uses these documents to delve into the immigrant experience with illuminating results, but perhaps a minor critique of the book could be made with the last few chapters, focusing on the social and cultural experiences of immigrants, which while certainly important, seem to feel a bit like a different book. That said, the chapters do help fill out the picture of immigrants in England, and they allow the authors to show how the interactions of official institutions with aliens and immigrants were perhaps some of the first glimmerings of nationalism, and in hindsight could be seen as a step in the development of the nation-state. The official tax records of the alien subsidy are a good example of the type of categorization that goes along with nationalist thought, i.e., who is English, and who is not English.

Immigrant England seems to skew toward being intended for more serious scholars as opposed to a general readership. Particularly if it is read in conjunction with the database website, it gives one a great deal of insight into conditions in England, and into evolving ideas of nationalism and ‘being English’ in the last centuries of the medieval period and the transition toward the early modern era.

Reviewed by Matthew Inman, George Mason University